"Wonder Woman has a message that goes far beyond the obvious theme of the exploitation of women".

Reg Livermore is posing questions about the relations of the sexes to the whole quality and nature of western society. What sort of men want to treat women this way? What sort of women are they to go along with such treatment? What sort of people are we and what sort of happiness do we achieve and do we deprive ourselves of? These are the sorts of questions that great theatre has always asked. To ask them in the context of pop songs and female impersonation reveals an artist of real genius." Rydge's, December 1976.

The success of Betty all over the country was sufficient inducement to begin preparing a new show almost immediately; barely pausing to catch my breath I opened in Wonder Woman at the Bijou in late September 1976. Apart from the good commercial sense in striking while an iron's hot I was now very much in demand. Also I had an idea. Unlike the seeming haphazardness surrounding the formation of Betty, I decided my next show would be about something: the Feminist Movement and the increasingly extreme profiles of some of its more outspoken standard bearers, a theme that was universal and wholly contemporary; as a premise for the show I was developing it was a gift. My intention was to depict women imprisoned in their personal and domestic situations, women as victims, and to liberate them: I then wanted to mark the trajectory of a 'new-age' feminist attitude pitting itself against the time-honoured male behaviour patterns observed and celebrated in this country with monotonous regularity. Finally I wanted to reverse their roles.

Wonder Woman premiered a little less certainly than Betty; the material was radically different and more effectively pointed, but not yet quite in place – maybe the audience found the show too much hard work. The enthusiasm for what I'd been offering around the country during the eighteen months just gone had led me to believe they'd be happy to go along with whatever I offered them. This was not the case; they still need to be entertained. Critical opinion was divided at the outset; there were suggestions that I'd gone too far this time, that I "wasn't performing any more", that I was approaching "a solitary orgasm". More perspicacious reviewers allowed that time and know-how would bring about necessary changes and improvements. The advantage of doing your own show is the freedom to ditch things that don't work, and in doing so perhaps come up with something that elevates a show to an entirely different level.

Enter Beryl at the sink. Vaseline Amalnitrate had been an important re-think in Betty, and subsequently became one of the show's highlights – it also had me almost booed off the stage when I presented him in London at the Phoenix Theatre in 1980; then I invented Beryl, the pair of them far outshining anything else in their respective programs, indeed they are the two monologues with which I'm indelibly associated. What intrigues me is that I've no idea where Beryl came from, how she happened, no memory of the process at all: I was in a hurry to replace a sketch that wasn't good enough, but what triggered my imagination? The context? Was it simply the notion of a chauvinist and his abnegation of domestic responsibility? Was I thinking about female slave status, the self-mockery inherent in addiction to housewifely duties? In terms of sharing the load, the balance and distribution is seriously uneven: once a week he hoses out the garage and mows the lawn, and every day she is doing the washing and ironing, and the cooking, and the cleaning, also bringing up the babies; and she's sleeping with him. For a woman so deferentially 'on call' the dramatically effective and universally understood phrase 'chained to the sink' is wryly appropriate. Taking the idea a few steps further then, the notion of being chained to the sink, actually manacled alongside a huge pile of dirty dishes, staring out the kitchen window towards a dispiriting view of snotty children playing in a neglected and undernourished vegetable garden is suddenly food for considerable thought. It must have developed along those lines, and little wonder when we meet this Beryl at her sink. She has also lately been receiving treatment at the hands of a psychiatrist. It was if it wrote itself actually. "How do you know so much about women", I was asked. "I imagine" was my usual and possibly guarded response.

The character line-up of Wonder Woman contained several of my personal favourites: Irene, an unloved bulk of flesh addicted to fridge raiding and pill popping, who begins each day with tea and toast and three Bex. "If you're going to feel good", she says, "you might as well feel nothing"; Carmen Marahuana is on drugs and lost to reality forever: the gas station proprietor Allison Diesel, a woman behaving as a man behaving as the woman in a stereotypical situation; and Wonder Woman herself, the only time I knowingly set out to address the female status for the sake of a joke – although it was not so far removed from the reality about to walk in on us. In tackling the lengths to which the argument of female liberation was currently being stretched, I thought I'd best create a suitably horrifying Wonder Woman on stage before people started reproducing them in birthing clinics. Basically I was a Paul Revere with the wind up me, galloping just ahead of militancy.

"Wonder Woman knows exactly who she is. She is Reg Livermore exploring the strange moon landscape of the supermarket, the secret yearnings lurking behind the baked beans, the spiritual consolations packaged by Bex. I don't think he always cares for what he sees in his multi-faceted mirror – but there it is. And that is why his audiences love to help him through it all, in the grand tradition of mateship. He pretends to be no more than what he is and gives all he can; and his audience gives it all back in affectionate support. It is in this extraordinary mixture of total vulnerability and the daring strength with which it is revealed that the secret of his undoubted star stature lies. When I last wrote Newsroom, and his Betty Blokk Buster Follies, I said he had to be a star, and a star in his own country. That's what he is, and this is where he lives." Dr Phillip Parsons.

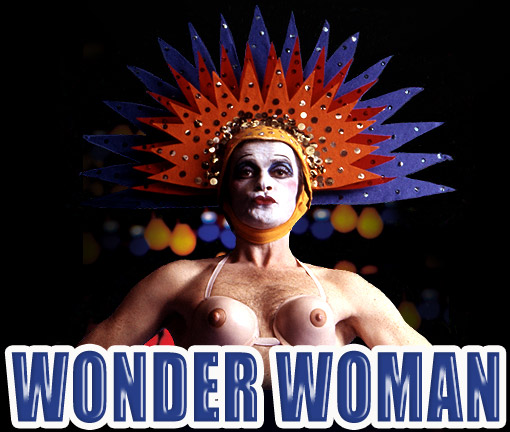

Photo: The Wonder Woman