" Super Reg ... Sensation of the night ... absolute show-stopper "

Hair buoyed me to the extent I couldn't conceive that anything might interfere with the momentum of my charmed career. But it did: first, the production of the musical I wrote with Sandra McKenzie and Patrick Flynn, Lasseter, a rare opportunity to bring a wholly Australian work to the stage sponsored by The Old Tote Theatre and directed by Jim Sharman that didn't hit its mark (nobody's fault but my own I suppose; a script that was simultaneously earnest and ludicrous); a disappointing and frustrating turn with the Melbourne Theatre Company playing opposite Nancye Hayes in three Noel Coward one act musical plays called Tonight at 8.30; and a lacklustre touring production through Fiji and New Zealand of the Michael Boddy/Bob Ellis play The Legend of King O'Malley.

By the time I'd put these away I was well and truly ready for another stint in Hair the show in which I'd spent such a happy and fulfilling two and a bit years; life outside of that show I discovered wasn't what I cared for. Sadly, neither were Hair and the Tribe when I returned to them, a case of absence making the heart fonder but the reality altogether depressing: infighting and malcontents had taken over the company, it was pretty much imploding. I'd signed for another six months, however, and it became clear I was only hanging out for something to come along and save me just as Hair had done. In the nick of time, Jesus Christ Superstar came along. (Thank God, you could say).

The show had been playing to packed houses at the Capitol Theatre in Sydney for a year or more, and was about to do the shift to Melbourne. A replacement for the show's King Herod was needed and it fell to me. It was one of those unbelievable theatre opportunities no doubt, presented on a platter like the head of John the Baptist: one song, one show-stopping moment (stage time – three and a half minutes). Marcia Hines had recently taken over from Michelle Fawdon as Mary Magdalene, and the acclaimed and long-awaited Harry M. Miller production arrived with the impact of an asteroid at the Palais Theatre in Melbourne's St Kilda where it would live for five full-house fabulous months. "Tell me what's the buzz? Tell me what's happening?" The building used to shake with excitement every night.

A show of that magnitude for which it is almost impossible to buy tickets incites the citizens: they are not unlike Romans at the Colosseum actually – (and the Palais Theatre almost as big as the Colosseum by the way) – the theatre's foyer swarming with a great crowd of jostling, frenzied people anxious to take their places inside to experience the spectacle and to cheer the hit show along. To find myself the object of their affection was something else; I had never had that kind of reception. Superstar is fairly turgid for much of its length, a long litany of religious pop and occasional pap; the King Herod song when it arrives three-quarters of the way through is a welcome relief. It must have proved an exceptional respite for the audience is all I can say; my Herod brought the house down every night without fail. I didn't quite appreciate how desperate they were for that moment, how grateful they'd be, all that stamping and cheering, hollering and falling about before returning perforce to the sterner stuff; they did, after all, have a pretty good idea of the plot, how it all had to end.

In the original Sydney season Herod arrived on stage in a battery-powered midget model car flanked by a bevy of sexy female tap dancers: a gimmick I thought, not really on a par with the rest of Jim Sharman's brilliant production. I wanted something different for my go at this role: I wanted to rise up out of the petals of the Brian Thomson designed dodecahedron as Jesus did in the first half, more like Shirley Bassey, however, rising up through the floor of the stage at the Talk of the Town nightclub in London. I was allowed to do it. The audience didn't have a clue what they were in for, whereas the car always gave it away: "Oh, a funny number!" But it's more than that: somewhere in Herod's short appearance I believe there has to be a sense of real threat. Those who saw me play Herod no doubt remember what I did, and how I did it; I'm not sure anymore. I do know the number's original running time increased by two and a half its length, at the end of the run it was nine minutes all up. The theatre always erupted when I came on for my bow, it was incredible, magnificent; I'd never been at the receiving end of such euphoria. Is it like that if you play in the grand final at the MCG I wondered?

Mind you, I must have been good; the newspapers were ecstatic about my contribution. 'Super Reg' …'Like the talented child or dog act, Reg Livermore as Herod must be a hard one to top. Almost as suddenly as he appeared he is gone, but in a few brief moments he has virtually stolen the show' …'Livermore's presence in any show is a bonus that lingers long after all else has been forgotten'.

Later, when the show played a return in Sydney …'It's not an exaggeration to say the new King Herod scene in Superstar is one of the most brilliant theatrical events in Sydney'.

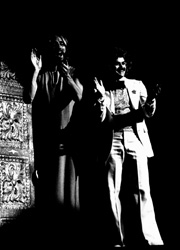

Photo: King Herod

Reg as King Herod, recorded live at The Capitol Theatre Sydney in 1973