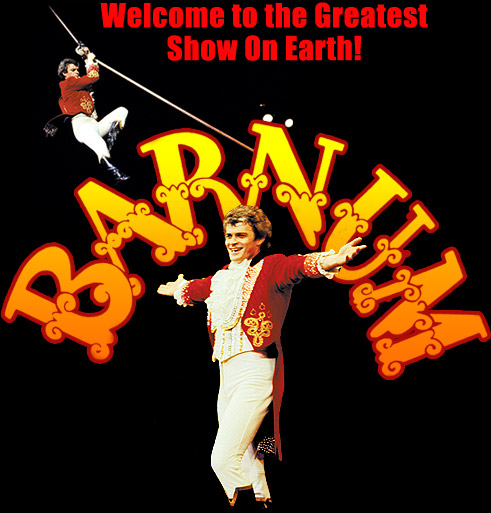

Book by Mark Bramble, lyrics by Michael Stewart and music of Cy Coleman Barnum was my first experience as the star of a hard-nosed Broadway Musical.

When the part of Phineas T. Barnum was offered I´d been licking my wounds in London, unsure as to my next move following the grand failure of my one man show there, Sacred Cow. Robert Helpmann believed I was the right man for the part and put my name forward to Michael Edgley who was already planning its production in Australia: ´if I was interested´ Edgley said he´d fly me across to New York to see it; I was particularly chuffed when he agreed to send me there by Concorde. After such a magnanimous gesture how could I refuse?

Anyway I enjoyed it, as the regular audience did. What I later discovered is that for the actor it´s a letdown. Beyond the first twenty minutes, the time it takes to introduce the main characters, there is scarce dramatic development; the script is minimal, and then abandoned completely as the show goes into musical overdrive; there is always a strong sense of jukebox, of pressing buttons, of being on automatic. It´s the songs that drive the action and for an actor who´s into exploring characterization and wringing out a couple of good speeches there can only be disappointment: eventually boredom.

The director and choreographer of the production here was Baayork Lee, an accomplished Broadway dancer who´d been one of the original cast members of A Chorus Line and indeed later directed that show in Australia. Baayork treated me very well, better than customary Australian theatre practice, certainly better than the imported Americans who were to direct me in The Producers some twenty-five years later.

My preparation for the role of Barnum involved six weeks´ training at the Big Apple Circus School in New York where I learned tight-rope walking, trampolining and juggling. My trainer was Alexandre ´Sasha´ Pavloski who´d put all the past and present Barnums through their paces; I was over the moon when Sasha said I picked up the wire walking as quickly as any of them; I was actually very good at it. In time I could settle on a knee, posing with one hand on the hip and the other high in the air, a flamboyant gesture that was as much self-congratulatory as it was bravura. If I was really centred I could easily strike an arabesque up there and it never failed to draw fulsome applause. Whatever I knew about dancing was the way to it: balance and the distribution of body weight, while the selective use of the arms was the key to keeping me upright, even the wiggle of a finger is enough to stop you falling. Actually I had to sing and walk simultaneously, but it was no death defying challenge since the rope was only two metres off the stage. If you knew you were about to take a tumble there were learned tricks that guaranteed you wouldn´t hurt yourself. The audience liked to see me struggle I noticed, may even have preferred it. On the odd occasions I did come off the rope, they were always much more appreciative of my second attempt, and in the very rare event I had to have a third go, they gave me the sort of reception marathon runners know when they eventually get to the line, as much for the last across as for the winner.

For my fans and supporters Barnum was not at all what they wanted to see me do, but as a means of putting the unforgettable London failure behind me it was the ideal antidote: working on stage with others for a change, not having to be solely responsible for the outcome. The audience who were very sympathetic to the bad reception given me in London no doubt would´ve preferred a show in which I got well and truly stuck into the bloody patronising Brits.

It pleased lots of other people though, and did my reputation no harm whatsoever: no swearing from my mouth, no drag, and no agendas, just good old-fashioned entertainment. On show every night was a leading man of exceptional athleticism, I looked dishy and appeared to be straight. Just forty-three years old, I was probably at my physical peak.

Photo: P.T Barnum